1.0 Historical Foundations of Psychometrics

The discipline of psychometrics emerged from two distinct yet complementary intellectual traditions. The first, championed by figures such as Charles Darwin, Francis Galton, and James McKeen Cattell, emphasized the study of individual differences and sought to develop systematic methods for their quantification. The second, rooted in the psychophysical research of Johann Friedrich Herbart, Ernst Heinrich Weber, Gustav Fechner, and Wilhelm Wundt, laid the foundation for the empirical investigation of human perception, cognition, and consciousness. Together, these two traditions converged to form the scientific underpinnings of modern psychological measurement.

1.1 Victorian Influence: Quantifying Individual Differences

The intellectual origins of psychometrics can be traced to Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory, which underscored the biological variability among individuals and its implications for adaptation and survival. Darwin’s insights spurred Francis Galton to investigate human differences in cognitive and sensory faculties, leading to his pioneering efforts in measuring intelligence. Galton’s seminal work, Hereditary Genius (1869), argued that intellectual abilities were largely inherited and could be assessed through objective methods. His development of statistical techniques, including correlation and regression, became cornerstones of psychometric analysis.

Building upon Galton’s foundation, James McKeen Cattell introduced the term mental test, signifying a structured approach to assessing cognitive capacities. Cattell’s emphasis on reaction time, sensory acuity, and other quantifiable traits represented an early attempt to establish standardized psychological assessments. His contributions significantly influenced the development of modern intelligence testing and the broader field of psychometrics.

1.2 German Contributions: The Birth of Experimental Psychology

While Galton and Cattell focused on the measurement of individual differences, German researchers advanced the study of mental processes through psychophysical experimentation. Johann Friedrich Herbart sought to apply mathematical principles to the study of consciousness, proposing that mental phenomena could be modeled through algebraic equations. His work had a lasting impact on educational psychology and instructional theory.

Ernst Heinrich Weber introduced the notion of a just-noticeable difference, quantifying the minimal perceptual change detectable by an individual. Gustav Fechner expanded upon Weber’s findings, articulating the principle that subjective sensation increases logarithmically with stimulus intensity—a formulation now known as Fechner’s Law. These discoveries established a quantifiable relationship between external stimuli and internal psychological experiences, a critical advancement in the scientific study of perception.

The culmination of these efforts occurred in the laboratory of Wilhelm Wundt, widely regarded as the father of experimental psychology. Wundt’s establishment of the first psychology laboratory in Leipzig in 1879 formalized psychology as an empirical science. His emphasis on systematic experimentation and introspective methods set the stage for the later development of psychometric assessments. Wundt’s influence extended to numerous researchers who would go on to refine psychological measurement techniques, integrating both experimental and statistical approaches.

By bridging the measurement of individual differences with the experimental study of cognition and perception, these early scholars laid the foundation for modern psychometrics. Their contributions provided the theoretical and methodological basis for the development of intelligence testing, personality assessment, and the broader scientific study of human abilities.

2.0 Defining Measurement in Social Sciences

The concept of measurement within the social sciences has long been a subject of methodological debate, reflecting broader philosophical and epistemological concerns about the nature of quantification in psychological and behavioral research. Unlike the physical sciences, where measurement entails the direct assessment of observable properties using standardized units, the social sciences frequently deal with latent constructs—abstract attributes that cannot be directly observed but must be inferred through structured assessment tools. This fundamental distinction has led to diverse perspectives on what constitutes a valid measurement framework in psychology and related disciplines.

A particularly influential conceptualization was proposed by Stanley Smith Stevens in 1946, in which he defined measurement as “the assignment of numerals to objects or events according to some rule.” Stevens’s definition diverged from the classical notion of measurement in physics, which typically requires the determination of a magnitude relative to a known standard. Instead, Stevens introduced a taxonomy of four levels of measurement—nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio—each reflecting different degrees of mathematical rigor. This hierarchical framework provided a systematic approach for classifying psychological and social science variables based on their permissible mathematical operations. While widely adopted in psychometric research, Stevens’s definition has also been criticized for its departure from the stricter measurement principles adhered to in the physical sciences.

A pivotal moment in this discourse occurred with the publication of the British Ferguson Committee’s 1932 report, which examined the feasibility of quantitatively assessing sensory events. The committee, composed primarily of physicists alongside several psychologists, underscored the difficulties in defining measurement within the domain of human perception and cognition. This report elicited varied responses from the scientific community. Some researchers contended that psychology should align itself with the physical sciences by adhering to the classical definition of measurement, thereby ensuring that psychological attributes were assessed with the same level of precision as physical properties. This perspective necessitated the development of measurement instruments that could produce data meeting stringent empirical criteria.

Conversely, proponents of Stevens’s broader definition argued that psychological phenomena, by their nature, could not always conform to the rigid constraints of classical measurement. Instead, they advocated for a more flexible approach that prioritized systematic quantification through rule-based assignment of numerical values. This perspective underpins many contemporary psychometric methodologies, including the use of covariance matrices and factor analysis to identify latent dimensions within psychological constructs.

The ongoing debate over the nature of measurement in social sciences remains central to psychometric theory, influencing test development, statistical modeling, and the interpretation of psychological data. While Stevens’s taxonomy continues to be widely applied, alternative measurement models—such as those based on item response theory and the Rasch model—have emerged to address concerns regarding the reliability, validity, and comparability of psychological measurements across different populations and contexts.

3.0 Instruments and Procedures in Psychometrics

The development of psychometric instruments has been driven by the need to quantify complex psychological constructs with empirical precision. From early intelligence testing to the refinement of personality and attitudinal assessments, psychometric methodologies have evolved to accommodate diverse domains of psychological inquiry. These instruments rely on rigorous statistical validation procedures to ensure their reliability, validity, and applicability across different populations and contexts.

3.1 Intelligence Testing: The Origins of Psychometric Assessment

The earliest psychometric instruments were designed to assess cognitive abilities, with intelligence testing serving as the foundation of modern psychological measurement. One of the most influential early contributions came from Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon, who, in the early 20th century, developed the Binet-Simon test in France. This assessment aimed to identify students requiring additional educational support by estimating their intellectual capabilities relative to their peers.

Building upon Binet and Simon’s work, Lewis Terman at Stanford University adapted the test for use in the United States, leading to the development of the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales. This revision introduced the concept of the intelligence quotient (IQ), providing a standardized metric for cognitive ability assessment. The Stanford-Binet test became a cornerstone of intelligence testing, influencing the creation of subsequent instruments such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC), both of which remain widely utilized in educational, clinical, and research settings.

3.2 Personality Assessment: Capturing Individual Differences

Beyond cognitive ability, psychometrics has played a central role in the systematic evaluation of personality traits. Unlike intelligence, personality is inherently multidimensional, requiring instruments that capture a broad spectrum of human behavior, cognition, and emotion.

One of the most extensively researched and applied personality assessments is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI). Originally developed in the 1940s and subsequently revised, the MMPI employs a comprehensive set of clinical scales to assess various psychological conditions and personality attributes. Its empirical approach, relying on statistical analysis rather than theoretical assumptions, distinguishes it from many earlier personality tests.

Another major development in personality assessment is the Five-Factor Model (commonly known as the “Big Five”), which organizes personality traits into five broad dimensions: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. The model, derived through factor analysis, provides a robust framework for understanding personality across cultures and contexts. Instruments such as the NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI) operationalize this model, offering a psychometrically sound method for personality assessment.

3.3 Attitudinal Measurement: Quantifying Subjective Beliefs

Psychometric methodologies have also been instrumental in assessing attitudes, which, while intangible, exert significant influence on human behavior. Attitudinal measurement requires scaling techniques that translate subjective opinions into quantifiable data. One of the most widely employed methods is the Likert scale, which presents respondents with a series of statements and asks them to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement on a structured continuum.

In addition to Likert scaling, Thurstone scaling and Guttman scaling provide alternative approaches to measuring attitudes. These techniques allow researchers to examine the intensity and consistency of beliefs, facilitating empirical investigations in fields such as social psychology, political science, and consumer research.

As psychometrics continues to advance, the refinement of assessment instruments remains a priority. Innovations in computerized adaptive testing, machine learning applications, and neuropsychological assessments promise to enhance the precision and applicability of psychometric tools, ensuring their continued relevance in psychological research and applied settings.

4.0 Theoretical Approaches in Psychometrics

The scientific measurement of psychological constructs necessitates robust theoretical frameworks capable of addressing the complexities inherent in human cognition, personality, and behavior. Psychometricians employ a range of measurement models, each designed to enhance the precision, reliability, and interpretability of psychological assessments. The choice of a specific theoretical approach depends on the nature of the construct being measured, the intended application of the assessment, and the statistical properties of the data generated.

4.1 Classical Test Theory: Foundations of Measurement

One of the most historically significant and widely used frameworks in psychometrics is Classical Test Theory (CTT). Rooted in early statistical models of psychological measurement, CTT posits that an individual’s observed score on a test is the sum of their true score and an error component. Mathematically expressed as:

X = T + E

where X represents the observed score, T is the true score, and E is the measurement error.

CTT provides foundational insights into test reliability and validity. A key assumption of this model is that measurement error is random and normally distributed, meaning that repeated measurements will approximate the individual’s true ability or trait level. Test reliability, often quantified using indices such as Cronbach’s alpha or test-retest correlation coefficients, serves as an estimate of the extent to which an instrument yields consistent results over repeated administrations. Despite its widespread application, CTT is limited by its dependence on sample-specific statistics, meaning that reliability estimates and item characteristics may vary across different populations.

4.2 Item Response Theory: A Probabilistic Approach to Measurement

In contrast to CTT, Item Response Theory (IRT) adopts a more sophisticated mathematical approach by modeling the probability of an individual’s response to a given test item as a function of their underlying latent trait level. IRT operates under the premise that test items vary in their difficulty, discrimination, and guessing parameters, and it seeks to estimate these parameters independently of the specific sample used.

A fundamental feature of IRT is its ability to generate item characteristic curves (ICCs), which describe the probability of a correct response as a function of an individual’s ability level. Unlike CTT, which assumes that measurement error is uniform across the entire score distribution, IRT allows for varying precision of measurement at different points along the latent trait continuum. This property makes IRT particularly advantageous in contexts such as computerized adaptive testing (CAT), where test items can be dynamically adjusted based on an examinee’s prior responses.

4.3 The Rasch Model: Objective Measurement Principles

A specific subset of IRT, the Rasch model, developed by Danish mathematician Georg Rasch, imposes strict measurement criteria to ensure that assessments produce invariant comparisons across different populations. Unlike other IRT models, which permit item parameters to vary freely, the Rasch model constrains item discrimination parameters to be equal across all test items. This constraint ensures that the measurement scale remains independent of the specific sample from which it was derived, thereby aligning psychometric measurement more closely with principles observed in the physical sciences.

The Rasch model’s emphasis on fundamental measurement principles has made it particularly useful in high-stakes testing environments, such as educational assessment and clinical diagnostics. The model’s requirements for unidimensionality and local independence ensure that the latent trait being measured remains conceptually pure, minimizing distortions introduced by extraneous factors.

4.4 Multivariate Statistical Techniques: Uncovering Latent Structures

Beyond the frameworks of CTT and IRT, psychometricians employ a range of advanced statistical techniques to analyze complex datasets and uncover latent psychological constructs. These methods include:

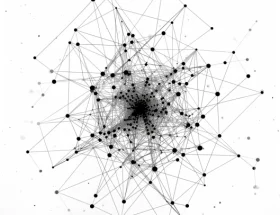

- Factor Analysis: A statistical method used to identify the underlying structure within a set of observed variables. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is employed when the dimensional structure of a construct is unknown, while confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) tests predefined theoretical models.

- Multidimensional Scaling (MDS): A technique that represents complex relationships among variables in a spatial format, allowing researchers to visualize similarities or dissimilarities between psychological constructs.

- Cluster Analysis: A method used to group individuals or items based on shared characteristics, aiding in the classification of psychological traits and behaviors.

These multivariate techniques are integral to psychometric research, as they enable the refinement of measurement instruments, the validation of theoretical models, and the identification of meaningful patterns within psychological data. As psychometric methodology continues to evolve, these statistical approaches remain indispensable tools in the quest for more accurate and meaningful psychological measurement.

5.0 Key Concepts: Reliability and Validity in Psychometric Evaluation

Psychometric measurement is fundamentally concerned with ensuring that assessment instruments provide meaningful, interpretable, and replicable results. The twin pillars of reliability and validity serve as the primary criteria by which the quality of any psychometric tool is judged. While reliability pertains to the consistency of a measure, validity addresses the accuracy and appropriateness of inferences drawn from test scores. A test cannot be valid unless it is reliable, but reliability alone does not guarantee validity—an instrument may yield consistent scores while failing to measure what it purports to assess.

5.1 Reliability: The Stability and Consistency of Measurement

Reliability refers to the degree to which a test produces stable and consistent results under varying conditions. A highly reliable test ensures that differences in scores reflect actual differences in the construct being measured rather than inconsistencies arising from external influences such as testing conditions, fatigue, or scoring errors. Various indices of reliability provide insights into different aspects of measurement consistency:

5.1.1 Test-Retest Reliability

Evaluates the stability of test scores over time by administering the same test to the same individuals on two separate occasions. High test-retest reliability indicates that the measure is resistant to temporal fluctuations and external disturbances.

5.1.2 Equivalent (Alternate) Forms Reliability

Assesses the consistency of two parallel versions of the same test. This approach is particularly useful in mitigating practice effects that may arise from repeated exposure to identical test items.

5.1.3 Internal Consistency

Examines the degree to which items within a test measure the same underlying construct. Common statistical indices include Cronbach’s alpha, which estimates the average correlation among test items, and the split-half reliability method, which involves dividing the test into two halves and correlating their scores.

5.2 Validity: Establishing the Meaningfulness of Measurement

Validity concerns the extent to which an instrument measures what it claims to measure and whether the interpretations drawn from test scores are theoretically and empirically justified. Psychometricians recognize multiple forms of validity, each addressing different facets of measurement accuracy.

5.2.1 Criterion-Related Validity

Examines the degree to which test scores correlate with an external criterion, assessing the practical utility of the measure. It is divided into two subtypes:

5.2.1.1 Concurrent Validity

Evaluates the relationship between test scores and a criterion assessed at the same time. For example, a new depression screening tool may be validated by comparing its scores to those from an established clinical interview.

5.2.1.2 Predictive Validity

Determines how well a test predicts future performance or behavior. The Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT), for instance, is intended to predict academic success in college.

5.2.2 Construct Validity

Addresses the degree to which a test accurately represents the theoretical construct it is intended to measure. Construct validation typically involves correlational analyses with other established measures, factor analysis to examine the underlying dimensions of the test, and experimental approaches assessing how scores vary across theoretically relevant conditions.

5.2.3 Content Validity

Ensures that a test adequately represents all facets of the domain it is designed to measure. This type of validity is particularly critical in educational and employment testing, where assessment items must comprehensively cover the required knowledge or skills. Content validation often involves expert review to confirm that the test items align with the intended construct.

5.3 The Interdependence of Reliability and Validity

Although reliability and validity are conceptually distinct, they are inherently interconnected. A test cannot be valid if it is unreliable, as unstable measurement precludes meaningful interpretation. However, a test may be highly reliable but invalid if it systematically measures an irrelevant or unintended construct. For example, a scale that consistently underreports anxiety symptoms would be reliable but lacking in validity.

Modern psychometric research emphasizes the importance of integrating multiple forms of validity evidence, ensuring that assessment tools provide both stable and meaningful measurements. Advances in statistical modeling, including structural equation modeling (SEM) and item response theory (IRT), continue to refine our understanding of these foundational psychometric principles, allowing for more precise and scientifically rigorous assessments.

6.0 Standards of Quality in Psychometric Testing

The scientific rigor and practical utility of psychometric assessments are contingent upon adherence to established quality standards. Ensuring that tests are valid, reliable, fair, and appropriately applied requires a structured framework of guidelines that govern test development, evaluation, and implementation. These standards serve to protect test-takers, enhance the interpretability of assessment results, and promote ethical testing practices across educational, clinical, and occupational settings.

6.1 The “Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing”

A foundational reference in psychometric quality control is the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing, published jointly by the American Educational Research Association (AERA), the American Psychological Association (APA), and the National Council on Measurement in Education (NCME). These standards provide comprehensive criteria for constructing, validating, administering, and interpreting psychological and educational assessments.

The Standards emphasize several critical dimensions of test quality, including:

- 6.1.1 Validity: The extent to which a test measures what it is intended to measure and supports appropriate interpretations of scores. The Standards outline the necessity of providing empirical evidence for various forms of validity, including content validity, construct validity, and criterion-related validity.

- 6.1.2 Reliability and Measurement Error: The degree to which test scores are consistent and free from excessive random variation. Guidelines stress the importance of reporting reliability coefficients, standard errors of measurement, and confidence intervals to contextualize test results.

- 6.1.3 Fairness and Accessibility: Ensuring that assessments do not systematically disadvantage individuals based on irrelevant factors such as language proficiency, cultural background, or disability status. This includes recommendations for bias detection, test accommodations, and inclusive test design.

- 6.1.4 Test Design and Administration: Best practices in item development, scaling procedures, and test administration protocols to minimize measurement error and enhance standardization.

- 6.1.5 Scoring, Reporting, and Interpretation: Guidelines for scoring methodologies, norm-referencing, and criterion-referencing, as well as best practices for reporting results to stakeholders in a transparent and interpretable manner.

The Standards are particularly influential in high-stakes testing environments, including educational admissions, professional credentialing, and clinical diagnostics, where the consequences of test-based decisions necessitate the highest levels of psychometric precision and fairness.

6.2 Educational Evaluation Standards

In addition to the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing, the Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation (JCSEE) has established specific criteria for enhancing the quality of educational assessments. The JCSEE has produced several sets of standards, including the Program Evaluation Standards, the Personnel Evaluation Standards, and the Student Evaluation Standards, each aimed at fostering rigorous and ethical evaluation practices in educational contexts.

The JCSEE’s guidelines emphasize four fundamental attributes of high-quality educational evaluations:

- 6.2.1 Propriety: Ensuring that evaluations are conducted ethically and with due regard for the rights and welfare of stakeholders. This includes considerations such as informed consent, confidentiality, and the responsible use of assessment results.

- 6.2.2 Utility: The degree to which an evaluation serves the needs of decision-makers and other stakeholders. Evaluations should be designed to produce actionable insights that inform instructional strategies, educational policy, or institutional improvement.

- 6.2.3 Feasibility: The practicality and efficiency of the evaluation process. This includes considerations related to cost, time, and resource availability, ensuring that assessment procedures are sustainable and proportionate to their intended purpose.

- 6.2.4 Accuracy: The extent to which evaluation findings are valid, reliable, and free from systematic bias. This entails rigorous methodology, appropriate statistical analyses, and careful consideration of confounding variables.

7.0 Controversies and Criticisms in Psychometrics

While psychometrics has significantly advanced the empirical assessment of psychological constructs, it remains a subject of ongoing debate and scrutiny. Detractors argue that the process of quantifying complex human attributes into numerical values inherently risks oversimplifying the intricacies of cognition, personality, and behavior. Concerns regarding the ethical use, validity, and societal implications of psychometric instruments continue to shape discussions in both academic and applied settings.

7.1 Reductionism and the Complexity of Human Behavior

A primary criticism of psychometrics is its reliance on numerical representation to capture psychological constructs that are inherently fluid, multidimensional, and context-dependent. Critics argue that reducing intelligence, personality, or emotional states to standardized scores may neglect important qualitative aspects of individual differences. While factor-analytic techniques allow for the identification of latent psychological dimensions, they do not necessarily capture the full richness of human thought, motivation, and environmental influence.

Moreover, psychometric instruments are constrained by the assumptions of their underlying statistical models. Classical Test Theory (CTT), for instance, assumes that measurement error is randomly distributed, while Item Response Theory (IRT) relies on probabilistic models that, despite their sophistication, remain dependent on item selection and sample characteristics. These limitations highlight the potential for distortion when psychological constructs are forced into rigid, numerical frameworks.

7.2 Misuse and Ethical Concerns in Applied Contexts

Beyond theoretical critiques, the application of psychometric tests in high-stakes decision-making has raised ethical concerns. In employment settings, for example, cognitive ability tests and personality inventories are frequently used for hiring and promotion decisions. While such assessments can provide valuable insights into candidate potential, their indiscriminate use may lead to adverse consequences.

7.2.1 Job Relevance and Construct Validity

A persistent issue is the extent to which psychometric tests align with actual job performance. If an assessment lacks predictive validity for workplace success, its use in hiring may be unjustified. The misapplication of intelligence or personality tests without consideration of contextual factors can result in flawed selection processes.

7.2.2 Bias and Fairness

Despite rigorous test development protocols, concerns remain about the potential for cultural, gender, and socioeconomic biases in psychometric instruments. Critics argue that some assessments may inadvertently disadvantage certain demographic groups due to differential item functioning or implicit biases in test construction.

7.2.3 Privacy and Consent

The increasing digitization of psychometric assessments raises questions about data security and informed consent. Individuals undergoing psychological testing may not always be fully aware of how their responses will be used, stored, or interpreted, particularly in corporate or governmental settings.

7.3 The Case of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)

Among the most contentious psychometric tools is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), a widely used personality assessment that classifies individuals into 16 distinct personality types based on dichotomous preferences (e.g., Extraversion vs. Introversion, Thinking vs. Feeling). Despite its popularity in corporate and personal development contexts, the MBTI has faced significant criticism from academic psychologists.

7.3.1 Lack of Empirical Support

Unlike personality models grounded in extensive factor-analytic research, such as the Five-Factor Model (FFM), the MBTI lacks strong empirical validation. Studies have shown that MBTI classifications often fail to demonstrate test-retest reliability, with individuals frequently receiving different personality types upon retesting.

7.3.2 Arbitrary Typologies

The binary categorization employed by the MBTI is inconsistent with contemporary psychological research, which suggests that personality traits exist on continua rather than discrete categories. By forcing individuals into rigid typological groups, the MBTI may oversimplify the complexity of personality.

7.3.3 Limited Predictive Utility

While the MBTI is often used for career guidance and team-building exercises, research has questioned its ability to predict workplace performance or interpersonal compatibility. Unlike validated instruments such as the NEO Personality Inventory, the MBTI lacks robust criterion-related validity.

7.4 The Need for Rigorous Validation and Ethical Application

The controversies surrounding psychometrics underscore the necessity of rigorous test validation, ethical application, and cautious interpretation of assessment results. While psychometric models provide powerful tools for understanding human attributes, they must be continually refined to account for theoretical, methodological, and ethical considerations. Ensuring that psychological assessments meet stringent validity, reliability, and fairness criteria remains an ongoing challenge—one that requires interdisciplinary collaboration between psychometricians, statisticians, and practitioners across diverse fields.

8.0 Cultural and Cross-Cultural Psychometrics

Psychometric assessments are inherently influenced by the cultural contexts in which they are developed and administered. While the field of psychometrics aspires to measure psychological attributes with objectivity and precision, concerns persist regarding the validity of these instruments across diverse populations. Many psychological tests, particularly those developed in Western contexts, have been criticized for embedding cultural assumptions that may not generalize to individuals from different linguistic, socioeconomic, or cognitive traditions. Addressing these challenges requires rigorous methodological strategies, including cross-cultural validation, differential item functioning (DIF) analysis, and the development of culturally fair assessments.

8.1 Challenges of Cultural Bias in Psychometric Testing

Cultural bias in psychometrics manifests in multiple ways, affecting the validity and fairness of assessments:

8.1.1 Construct Bias

Occurs when a psychological construct is not equivalent across cultures. For example, the concept of intelligence may be viewed differently across societies, with some cultures emphasizing analytical reasoning and others prioritizing social or practical intelligence. If a test assumes a Western conceptualization of intelligence, it may fail to capture cognitive abilities valued in non-Western populations.

8.1.2 Method Bias

Arises from differences in test administration, response styles, or familiarity with test formats. For instance, individuals from collectivist cultures may respond differently to self-report personality assessments compared to those from individualist cultures, leading to systematic variations that are unrelated to the underlying construct being measured.

8.1.3 Item Bias (or Differential Item Functioning, DIF)

Occurs when individuals from different cultural groups with the same underlying ability or trait level respond differently to specific test items. For example, a verbal reasoning test may contain idiomatic expressions or culturally specific references that disadvantage non-native speakers, introducing systematic bias in test scores.

8.2 Differential Item Functioning (DIF) and Bias Detection

To identify and mitigate cultural bias, psychometricians employ Differential Item Functioning (DIF) analysis, a statistical technique that examines whether test items function differently across groups when controlling for the underlying trait being measured. DIF can be detected using:

8.2.1 Mantel-Haenszel methods

which compare item difficulty levels between different demographic groups.

8.2.2 Item Response Theory (IRT)-based approaches

which evaluate whether test items maintain the same measurement properties across populations.

8.2.3 Structural equation modeling (SEM)

which tests whether the same latent construct structure holds across different cultural groups.

8.3 Developing Culturally Fair Assessments

Efforts to enhance the cultural fairness of psychometric assessments involve multiple strategies:

8.3.1 Linguistic and Conceptual Adaptation

Translating and adapting test items through rigorous cross-cultural validation procedures, rather than direct linguistic translation, to preserve meaning across languages. The International Test Commission (ITC) has established guidelines for test adaptation to maintain construct equivalence across languages and cultures.

8.3.2 Emphasis on Nonverbal Measures

Intelligence tests such as the Raven’s Progressive Matrices, the Jouve-Cerebrals Test of Induction (JCTI), and the Cattell Culture Fair Intelligence Test (CFIT) reduce linguistic dependency by using abstract reasoning tasks, thereby minimizing language-related biases.

8.3.3 Norming Across Diverse Populations

Establishing representative norm groups across different cultural contexts ensures that test scores are interpreted in a culturally appropriate manner.

8.3.4 Cultural Sensitivity in Test Development

Involving experts from diverse backgrounds in the test construction process to ensure that items are free from implicit biases and culturally specific assumptions.

8.4 Future Directions in Cross-Cultural Psychometrics

As globalization increases the diversity of test-taking populations, psychometrics must continue refining methodologies to ensure fairness and validity across cultural groups. Advances in computerized adaptive testing (CAT), artificial intelligence-driven test adaptation, and dynamic assessment approaches hold promise for reducing cultural bias by personalizing assessments to individual cognitive and linguistic backgrounds.

Ultimately, cultural and cross-cultural psychometrics aim to uphold the integrity of psychological measurement by ensuring that tests provide accurate, meaningful, and equitable assessments across all populations, irrespective of cultural background.

9.0 Applications of Psychometrics in Specific Fields

Psychometrics serves as a foundational discipline across numerous domains, providing standardized methods for assessing cognitive abilities, personality traits, psychological disorders, and behavioral tendencies. While educational testing, clinical psychology, and personnel selection remain primary areas of application, psychometric principles extend into specialized fields such as neuropsychology, forensic psychology, and organizational behavior, where precise and valid measurements are essential for decision-making, intervention planning, and legal or professional accountability.

9.1 Neuropsychology: Assessing Cognitive Function and Brain Integrity

Neuropsychology relies heavily on psychometric assessments to evaluate cognitive function in individuals with neurological disorders, brain injuries, or neurodevelopmental conditions. Standardized tests measure various domains of cognitive ability, including attention, memory, executive function, and language processing.

9.1.1 Cognitive Impairment and Dementia Screening

Tests such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) are widely used to detect early signs of cognitive decline in aging populations, aiding in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

9.1.2 Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and Stroke Assessment

Neuropsychological batteries, such as the Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery and the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS), provide objective measures of cognitive deficits resulting from brain injuries, stroke, or neurodegenerative conditions.

9.1.3 Developmental and Learning Disorders

The NEPSY-II and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-V) assess cognitive and executive functioning in children with suspected neurodevelopmental disorders such as ADHD, dyslexia, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Neuropsychometric testing plays a crucial role in diagnosis, rehabilitation planning, and monitoring cognitive changes over time, ensuring that interventions are tailored to an individual’s specific cognitive profile.

9.2 Forensic Psychology: Psychometrics in Legal and Criminal Contexts

In forensic psychology, psychometric assessments provide objective data in legal proceedings, informing decisions related to criminal responsibility, competency, risk assessment, and psychological damages.

9.2.1 Competency and Criminal Responsibility Evaluations

Courts frequently rely on psychometric instruments to assess whether an individual is competent to stand trial or criminally responsible for their actions. Tests such as the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool help determine an individual’s understanding of legal proceedings and their ability to participate in their defense.

9.2.2 Risk Assessment for Violence and Recidivism

Tools like the Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) and the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG) estimate the likelihood of violent behavior or recidivism in criminal populations, aiding in parole decisions and risk management strategies.

9.2.3 Child Custody and Psychological Injury Claims

Family courts use psychometric tests to assess parental fitness and child well-being in custody disputes. Similarly, psychological assessments such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2) help evaluate claims of psychological distress in civil litigation cases.

9.3 Organizational Behavior: Enhancing Workplace Productivity and Leadership

In industrial and organizational psychology, psychometrics plays a key role in optimizing employee selection, leadership assessment, and workplace dynamics. Psychological measurement helps organizations identify candidates with the right cognitive and personality traits for specific roles, develop leadership potential, and assess job satisfaction and motivation.

9.3.1 Personnel Selection and Talent Assessment

Employers use cognitive ability tests, such as the Wonderlic Personnel Test or the Raven’s Progressive Matrices, to evaluate problem-solving skills and learning potential. Personality inventories, such as the Big Five Personality Test and the Hogan Personality Inventory (HPI), help predict job performance and cultural fit.

9.3.2 Leadership Development and Executive Assessment

Leadership assessments such as the California Psychological Inventory (CPI) and the Korn Ferry Leadership Architect evaluate traits associated with effective leadership, aiding in executive coaching and succession planning.

9.3.3 Workplace Well-Being and Employee Engagement

Surveys measuring job satisfaction, burnout, and organizational commitment—such as the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)—inform HR strategies for improving workplace morale and reducing turnover.

9.4 Expanding the Scope of Psychometric Applications

Beyond these domains, psychometric principles are increasingly applied in fields such as health psychology (assessing patient-reported outcomes), sports psychology (evaluating mental resilience in athletes), and consumer psychology (measuring brand perception and decision-making tendencies). As psychometric methodologies continue to evolve, their influence extends into emerging areas, ensuring that psychological measurement remains integral to decision-making across diverse professional and scientific disciplines.

10.0 Expanding Horizons: Non-Human Applications of Psychometric Principles

Although psychometrics has historically been confined to the assessment of human cognitive and psychological attributes, emerging research has begun to extend its principles beyond traditional boundaries. Increasingly, psychometric methodologies are being applied to non-human subjects and artificial systems, facilitating the systematic measurement of cognitive abilities, learning processes, and behavioral tendencies across species and machine intelligence frameworks.

10.1 Comparative Psychology and Cross-Species Measurement

The field of comparative psychology investigates the cognitive and behavioral processes of non-human animals, employing experimental and psychometric techniques adapted from human studies. Researchers in this domain seek to quantify interspecies differences in problem-solving abilities, memory, social cognition, and emotional regulation.

10.1.1 Cognitive Testing in Non-Human Primates

Studies on primates, particularly great apes, have demonstrated parallels between human and non-human intelligence, often utilizing structured assessments analogous to those used in human psychometrics. Tasks involving sequential learning, object permanence, and numerical cognition have revealed cognitive competencies in species such as chimpanzees and orangutans, supporting evolutionary theories of intelligence.

10.1.2 Personality Measurement in Animals

Just as psychometric instruments assess human personality traits, researchers have developed behavioral rating scales to evaluate stable dispositional tendencies in animals. The Five-Factor Model (FFM) has been adapted to study personality in species ranging from domesticated dogs to non-human primates, demonstrating that dimensions such as extraversion, neuroticism, and agreeableness have cross-species relevance.

10.1.3 Learning and Adaptive Behavior

Classical and operant conditioning paradigms have long served as experimental frameworks for assessing animal learning. More recently, psychometric modeling techniques, including latent trait analysis and Bayesian inference, have been employed to measure decision-making strategies, reinforcement learning, and environmental adaptability in non-human subjects.

10.2 Machine Intelligence and Computational Psychometrics

In addition to biological entities, psychometric principles are increasingly being applied to artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning systems. The emerging field of computational psychometrics seeks to develop objective frameworks for evaluating the cognitive capabilities of AI models, drawing parallels between human intelligence assessment and machine learning performance metrics.

10.2.1 General Intelligence in Artificial Systems

Traditional intelligence tests measure human cognitive functions such as reasoning, problem-solving, and pattern recognition. Efforts to create analogous assessments for AI systems involve evaluating algorithmic efficiency, adaptability to novel tasks, and capacity for autonomous learning.

10.2.2 Universal Psychometrics

Some researchers advocate for a unified approach to measuring intelligence across humans, animals, and machines. Universal psychometrics aims to establish standardized metrics that account for differences in processing architecture, sensory modalities, and problem-solving strategies across diverse cognitive systems.

10.2.3 AI-Based Personality and Behavior Prediction

Advances in natural language processing and machine learning have enabled AI-driven psychometric assessments, where algorithms analyze linguistic patterns, social media activity, and biometric data to infer personality traits, emotional states, and cognitive styles. While such applications hold promise for areas such as mental health diagnostics and behavioral prediction, ethical concerns regarding privacy, consent, and algorithmic bias remain critical considerations.

10.3 The Future of Non-Human Psychometric Applications

As psychometric methodologies continue to evolve, their extension beyond human assessment presents both opportunities and challenges. Cross-species cognitive testing can refine our understanding of intelligence and behavior, while AI-driven psychometrics offers novel insights into artificial cognition. However, these applications also necessitate rigorous methodological scrutiny to ensure that measurement principles remain scientifically valid, ethically sound, and free from anthropocentric biases.

The expansion of psychometrics into non-human domains underscores the discipline’s adaptability and interdisciplinary relevance. Whether applied to animals, AI systems, or hybrid human-machine interactions, the fundamental principles of measurement, validity, and reliability remain central to the pursuit of objective psychological and cognitive assessment.

Conclusion

Psychometrics has established itself as an indispensable discipline within psychology and the social sciences, offering systematic methodologies for quantifying latent psychological attributes with empirical rigor. From its historical foundations in intelligence testing and psychophysical research to its contemporary applications across neuropsychology, forensic psychology, organizational behavior, and artificial intelligence, the field continues to evolve in response to theoretical, methodological, and ethical challenges.

Despite its advancements, psychometrics is not without controversy. Concerns regarding cultural bias, construct validity, and the ethical implications of psychological measurement highlight the importance of continuous refinement in test development and application. Rigorous validation, adherence to professional testing standards, and the development of culturally fair assessments remain central to ensuring that psychometric tools provide meaningful and equitable insights across diverse populations.

As technology reshapes the landscape of psychological assessment, the integration of artificial intelligence, computerized adaptive testing, and advanced statistical modeling presents new opportunities and challenges. However, the core principles of psychometrics—reliability, validity, fairness, and interpretability—remain unchanged, guiding the field toward greater precision and ethical responsibility in psychological measurement.